Early Postwar Voices: David Boder's Life and Work

by Alan Rosen

David Boder was born to Berl and Betti Michelson on November 9th, 1886, the fifth of what was to be seven children. His given name was Aron Mendel (the name "David Boder" was taken considerably later). The Michelson family resided in the city of Libau (Liepaja), a significant port on the Baltic Sea in an area of Latvia known as the Courland. At the time of Boder's birth, Libau and the Courland had been under Russian rule for nearly a century. Libau's Jewish population was considerable, in spite of the fact that the Courland was outside of the Russian Pale of Settlement, the only area in Imperial Russia where Jews could legally reside. Hence he grew up in a burgeoning Jewish community, residing with friends among whom he would have likely spoke in Yiddish or German, reserving Russian for the classroom.

His first place of study was probably one of Libau's two Jewish government schools, featuring a mixed curriculum of religious and secular classes. For advanced education, the Courland Jewish community sent its boys to nearby Lithuania, in Boder's case to the Jewish Teacher's Institute in Vilna, where he studied from age thirteen to age eighteen or nineteen. Here too classes were in secular and religious topics, with an emphasis on Russian and Hebrew grammar, Jewish history, and the Bible.

Upon graduation, Boder chose a different path from most of his classmates, leaving Russia and heading west to Leipzig, Germany, where he spent six months studying with Wilhelm Wundt, one of the aging but eminent pioneers of modern psychology. His time with Wundt likely introduced him to laboratory experimentation and the notion of scientific research in general, and had a hand in moving him to make psychology his vocation.

Boder also took advantage of his westward momentum to travel for the first time to the United States, spending four weeks in New York in the summer of 1906. The visit undoubtedly exposed him to a vast immigrant population unlike any he had encountered before, and may have had a lasting impact: later on, in the aftermath of the World War II, Boder advocated passionately on behalf of Jewish immigration to America, fueled by belief that America could absorb and would benefit from such immigration.

In any event, Boder's early travels pointed him toward a career in psychology. To obtain the necessary credentials, he headed to St. Petersburg, spending the next five years at Vladamir Bekhterev's Psychoneurological Institute, where, in contrast to the Russian universities, Jewish students did not face a rigid quota. These years also likely exposed him to the city's state-of-the art ethnography, particularly that which endeavored to chronicle Jewish culture trying to survive Czarist oppression. Professionally invigorating, the time in Petersburg was personally turbulent. He was married in 1907 to Pauline Ivianski, and a daughter was born later that year. But the couple divorced not long after, for what Boder later cited as "personal reasons." The daughter, Elena, was under her father's care from the time of the divorce, and the two forged a relationship that was to be a compass point of Boder's nomadic life.

The Great War brought vast changes to Boder's situation, as it did to European Jewry and the world at large. A twenty-seven-year-old gymnasium instructor when the war broke out in August 1914, by the next year he was working with a Russian engineering army battalion, his age and education landing him a kind of supervisory role with a "semi-civilian" officer rank thrown in for good measure. In 1917, as the war continued and the turmoil of Russian society reached a fever pitch, Boder went east to Omsk, Siberia, where he ostensibly served as the Director of Adult Education for the Trans-Siberian railroad. The time in Omsk ushered in yet another change in Boder's domestic life when he wed for a second time, to Nadejda Chernik, ten years after his first marriage.

The real upheaval came in 1919, when Boder, with his new wife and daughter Elena in tow, fled east to escape the ravages of the Russian civil war, finding refuge first in Japan and subsequently in Mexico. The refuge turned sour several months later when Nadejda died in the great flu epidemic that claimed 25 million victims worldwide. He nevertheless persevered in fashioning a new life in the new world, lecturing at the National University in Mexico City, directing psychological research for the Mexican prison system, supervising testing services for several government colleges, and even founding a short-lived psychology journal—all in a Spanish acquired with breathtaking ease. He was professionally busy, and had his finger in many pies, probably because none on its own could make ends meet.

Having lost his second wife almost as soon as he came to Mexico, Boder concluded his stay there by marrying for the third time, in 1925. His new bride, Dora Neveloff, had been born in Russia but had come to America at an early age and was a naturalized U.S. citizen. She was a year older than Boder and was by training a dentist. Unlike the previous two marriages, this one would last. Maintaining an independent career, Dora would lend her skills and talents, especially her knowledge of languages, to furthering her husband's work. While in Mexico Boder had traveled to America regularly, likely weighing the possibility of emigration from early on. After marrying Dora, who had a large extended family north of the border, it made professional and familial sense to relocate.

Once settled in the U.S., Boder quickly established himself. He obtained an MA from the University of Chicago in 1927, with a thesis on the psychology of language, and a PhD from Northwestern in 1934, with a dissertation on a specialized aspect of physiological psychology. Meanwhile, he was hired at the Lewis Institute (a forerunner of Illinois Institute of Technology), helping to develop its psychology department, and in the mid-1930s, with an eye towards popularizing what was then an arcane discipline, he launched a Psychology Museum. He was clinically busy as well, on staff at Michael Reese Hospital and the Institute for Juvenile Research. He continued a balancing act between the old and new worlds, becoming a U.S. citizen in 1932, but traveling and corresponding regularly with family and colleagues in Europe. At the outbreak of World War II in 1939 and America's entry two years later, Boder, too old to serve in the military, contributed to the war effort by publishing a manual on Morse Code, dissecting the perils of Nazi science in one trenchant article, and setting out the wartime role of psychology in another. In terms of the fate of European Jewry, he knew more or less what any emigré academic did.

The war's end set in motion the beginning of an endeavor that would define Boder's work for the rest of his life. He himself marked the germination of the displaced persons (DPs) interview project as May 1945, "shortly after the peace treaty was signed." He had hoped to travel in the summer of 1945, but he ended up spending the next fourteen months getting approval for the visit to Allied-occupied Western Europe, refining the conceptual basis of the interview project, and raising funds to finance the journey (though he viewed funding as a secondary concern). As late as June 1946, it was still not clear if he would be going. But approval, concept, and funding finally came together for him to set sail in late July aboard the USS Brazil, a ship contracted by the United States Government to convey delegates to the Paris Peace Conference, which was also scheduled to get underway at the end of July and the duration of which, incidentally, nearly paralleled the nine weeks of Boder's expedition.

His goals were straightforward. First of all, he wanted to preserve an authentic record of wartime suffering. Second, he was professionally interested as a psychologist in the impact of extreme suffering on personality. Third, he wanted to increase the knowledge of a post-war American public who knew little about what happened to the victims in the ghettos and in the concentration camps. And finally, he hoped that the DPs' stories could be effective in advocating on their behalf for immigration to America.

Arriving in Paris in late July, Boder would spend the next two months interviewing 130 displaced persons in nine languages and recording them on a state-of-the-art wire recorder. The interviews were among the earliest (if not the earliest) audio recordings of Holocaust survivors. They are today the earliest extant recordings, valuable not only for the testimonies of survivors and other DPs, but also for the song sessions and religious services that Boder recorded at various points during the expedition.

Boder's itinerary included four countries—France, Switzerland, Italy, and German—and sixteen different interview sites. On most days he conducted between two and five interviews, with each interview lasting anywhere from 20 minutes to several hours. As the weeks went by and Boder sensed his time drawing short—he was obliged to return to Chicago for the fall semester—he stepped up the pace. Toward the end, he completed as many as nine in a single day. This withering day of interviews took place on September 21, in Munich. That breakneck pace was even beyond what Boder could maintain, and most days total half that number. Some days are unaccounted for. Boder left Europe in early October, having recorded over ninety hours of material and completely used up the two hundred spools of wire that he had brought with him.

Most of the interviews were conducted with Eastern European Jews, and of these the majority were from Poland. Yet Boder was keen on speaking to many different kinds of groups: Western European Jews (including six Greek Jews that did not fit neatly in either category) number close to twenty. His interviewees thus covered the extreme ends of the spectrum of modern Jewish experience, from passionately Torah-observant Jews who hailed from great yeshiva centers in Lithuania, to assimilated German Jews married to non-Jewish spouses. Most, however, fell somewhere in between. When it came to war time experience, the greater part—whether Eastern or Western, Hungarian or Greek—had ended up in labor or concentration camps. The terrible rigors were what Boder believed his American audience needed an education about: "We know very little in America about the things that happened to you people who were in concentration camps," was how Boder would orient his narrator to the task and purpose of the interview. But such a mandate did not stop Boder from interviewing over twenty Jews who had not been in the camps. Their stories—of enduring the privation of ghettos, of hiding in woods or on farms, of fleeing to or fighting for Russia—presumably qualified as the "not unusual stories" that Boder said he was seeking and could similarly perform the task of educating an audience across the ocean.

This variety of experience was no doubt important and, at least in terms of the breadth of nationalities and interview languages, atypical when compared to other post-war interview projects. But more remarkable still was the inclusion of twenty-one non-Jews, approximately nineteen percent of the interviews. To be sure, most of these interviews took place only once Boder had arrived in Germany and had access to a larger pool of DPs. Had he not received the clearance to travel to Germany, his constituency would look much more like other interview projects from this period. But this assessment is itself in need of nuance. Non-Jewish DPs appear on Boder's interview slate from early on, with three such interviews (Czolopicki, Marson, and Rudo) taking place at the first Paris interview site. And in the planning stages of the trip, Boder intended to include an even broader sample of non-Jews, including perpetrators and Germans who resided in the proximity of concentration camps.

Boder also highlighted the experiences of children and youth. Three interview sites were geared especially for young DPs: two (Chateau Boucicaut and ORT Geneva) for "Buchenwald children" and the third (Bellevue) an orphanage transplanted from Poland to France, headed by the legendary Lena Kuechler. Over all, thirty-three of Boder's interviewees were twenty-five years-old or under, and of those, at least sixteen were under twenty. A substantial thirty percent of the interviewees were still teenagers during the war.

When he returned to the U.S. in October, Boder was busy with honoring his commitment to teach the fall semester at IIT. But the aftermath of the trip pressed him with obligations of its own. He gave talks, lectured, made contact with relatives of the interviewees and, on occasion, arranged for them to hear the voices of their loved ones recounting what had happened. But voices were not enough, and Boder set about transcribing the interviews soon after his return. By 1947 came the publication of the first excerpt; by 1948, astonishingly, a book manuscript was ready. Yet this too was not enough. In order to demonstrate the significance of the horrors recounted, Boder had to submit them to analysis, setting forth a kind of commentary on word and narrative as well as codifying them in terms of the kind of trauma suffered. All these efforts were encouraged and supported by his professional community, including the first of what would become a series of grants from the National Institute of Mental Health.

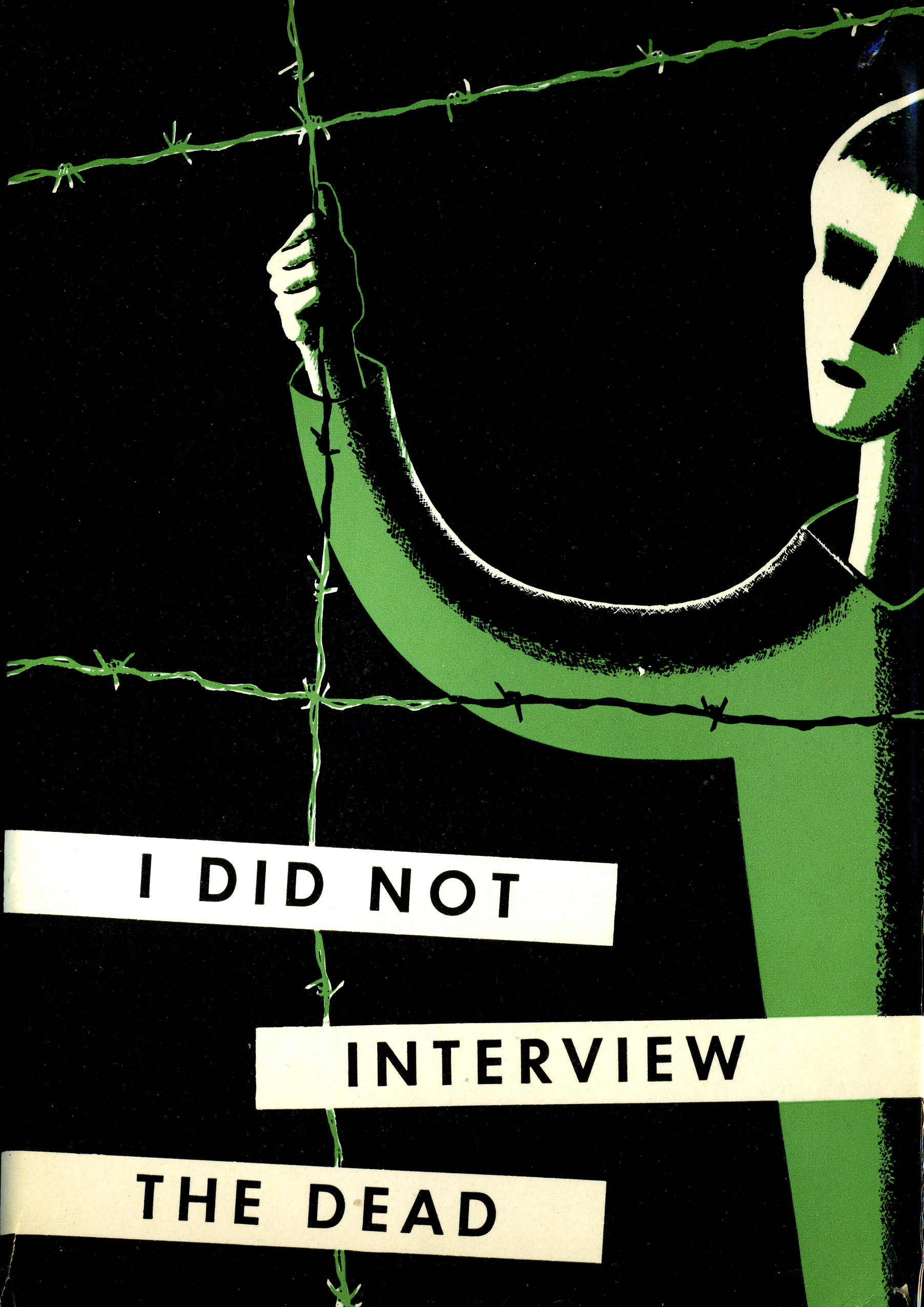

The book that grew out of the project, containing a selection of transcribed interviews and a modicum of analysis, was in manuscript called "The D.P. Story" and eventually published under the title, I Did Not Interview the Dead. Boder was already prospecting for publishers in the summer of 1947; a commitment came only in the spring of 1949, and the book appeared later that year. By December Boder was sending copies to friends, colleagues and potential reviewers.

This period, bountiful in so many ways, also took a toll. In November 1949, close to his 63rd birthday, Boder suffered a heart attack (a "seizure of coronary" in his own ponderous phrasing). He spent some time in the hospital but, responding well to treatment, was back to work in a matter of months. He also went further with the interviews, bringing out the first series of Topical Autobiographies, his self-published transcriptions of seventy interviews (subsequent volumes appeared in 1953, 1955, 1956, and 1957). There were clearly trade-offs in turning to self-publishing. On the one hand, Boder lost the imprimatur of a press and the associated publicity; his self-published volumes were never reviewed. But on the other hand, he gained the freedom to do as he pleased.

In the summer of 1951, Boder again interviewed displaced persons, this time victims of a huge flood in Kansas City. He was hoping to collect data that would let him compare the traumatic impact of "natural" with "man-made" disaster, a project that found important if brief expression in his writings. Soon after his return he was advised for reasons of health not to spend another winter in Chicago. Boder retired from IIT in 1952 and arranged to be based as a Research Associate in the psychology department at the University of California, Los Angeles, where supported by the NIMH grant he continued working on the DP interviews. In Chicago, Boder left behind dedicated students, who had helped him process the DP interviews and launch serious study of them. But he had the good fortune in Los Angeles of finding others.

The move to Los Angeles maintained the project's momentum. Two years after arriving at UCLA Boder published "The Impact of Catastrophe," his major essay devoted to analyzing the interviews. The article appeared in 1954 in the Journal of Psychology, and brought together many of Boder's psychological concerns: language, trauma, comparative catastrophe, and the personal document. Boder clearly saw the article as a milestone.

By 1956, the time-consuming occupation of transcription had run its course. Boder had to come to terms with the end of the NIMH funding that had supported his work for nearly ten years. In retrospect, he had underestimated both time and expense:

In dealing with procedures at least technically without precedent, the investigator, in applying for funds, was unable from the start to envision the great complexity involved in the task, and to make accordingly a more precise estimate as to costs, or time required for the full completion of the project. (March, 1957)

Boder nevertheless kept pursuing with characteristic industry and imagination other avenues of support for the project, one of which was an ambitious plan to transfer the project to Israel, where he believed the linguistic diversity of the country's population would be conducive to transcribing the interviews in their original tongues, and where the project's Jewish cast would receive its full expression.

A few years later, the health condition that had afflicted Boder for over a decade finally caught up with him. He died of a heart attack in his Los Angeles home on the morning of December 18, 1961. His wife Dora lived until 1975; his daughter Elena, who had no children of her own, until 1995. In his wake, Boder left a monumental library of early postwar voices, guided by his own.

(A more lengthy version of David Boder's biography is available in Alan Rosen's The Wonder of Their Voices: The 1946 Holocaust Interviews of David Boder, New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.)